Mangrove forests are one of Australia's most geographically widespread ecosystems. They provide a crucial role in the protection of Australia's coastline as well as being vital for the biological health and productivity of Australia's coastal waters.

Mangroves do not belong to a single taxonomic group, rather it is the name given to a group of plants that are all adapted to live in the intertidal zone (between the average sea level and the high tide mark). Mangroves include a wide variety of species including shrubs, palms, ground ferns, climbers and grasses.

There are 15.5 million hectares of mangroves worldwide (Figure 1). Australia is surrounded by 0.9 million hectares, of mangrove-lined coast – the third largest area of mangroves in the world after Indonesia and Brazil. Although mangroves cover less than one per cent of Australia’s coastline and 6.4 per cent of the world’s total mangrove area, Australia has the fourth highest species diversity of all countries with 41 species from 19 plant families, representing 57 per cent of species found in the world. Mangrove areas are highly fertile habitats, supporting a rich diversity of animal species.

Mangroves occur naturally in most coastal areas of Western Australia from Shark Bay northwards. The diversity of mangroves diminishes markedly from north to south and only one species is found at Shark Bay and further south.

As a result of varying environments and conditions, including climate, tidal ranges, temperature and rainfall, these mangroves are quite different from elsewhere in Australia. In Western Australia, mangroves are most common in the Kimberley and Pilbara regions, Exmouth, and Shark Bay. There are also some small and isolated communities at the Abrolhos Islands in the State’s mid-west and in the Leschenault Inlet, Bunbury in the State’s south-west.

Western Australia can be split into five regions (Figure 2) based on the number of types of mangrove habitat (adapted from MangroveWatch 2010).

Figure 2. Western Australia is split into five regions based on the types of mangrove habitat. (Map: Duke, N.C. Australia’s mangroves)

Adaptations

A mangrove is a land plant that is able to live in salt water. Plants growing in intertidal and estuarine habitats are highly specialised and have adapted to colonise and thrive in these areas. They experience large fluctuations in salinity: being inundated by seawater (high salinity) during high tides, while at low tide, or during heavy rains or floods, they can be exposed to open air or fresh water (low salinity). They have developed particular ways of dealing with concentrations of salt that would kill or inhibit the growth of most other plants.

Figure 3. Mangroves are land plants exhibiting adaptations that allow them to live in salt water (Image: © Shannon Conway)

Leaves and bark for desalination

The water available to mangroves is usually salty, but the plant needs to desalinate it so it can be used. Membranes in cells at the root surface exclude most of the salt but some salt still enters the root system.

- In some species, this passes through the plant and is stored within the plant in its leaves, stems and roots.

- In others, salt is secreted by special leaf glands where the salt is stored until the leaf dies and is shed (Figure 4).

- A third method of coping with salt is to concentrate it in the bark or older leaves which carry it with them when they drop.

Leaves for conserving water

Because of the limited availability of fresh water in the salty soils of the intertidal zone, mangrove plants conserve the amount of water they lose through their leaves. They can restrict the opening of their stomata (small pores on their leave surfaces which exchange carbon dioxide gas and water vapour during photosynthesis) and also have the ability to tilt their leaves (Figure 5). By orientating leaves to avoid the harsh midday sun, mangrove plants can reduce evaporation from their leaf surfaces.

Oxygen for roots

A supply of oxygen to the roots is vital for plant growth and nutrient uptake. Mangroves have extensive underground root systems that support and anchor the plants. Because mangrove soils are often anaerobic (lacking in oxygen), mangrove plants can’t rely on these underground roots to absorb oxygen like other terrestrial plants. Therefore, many mangroves have adapted aerial roots above the mud (Figure 6) – specialised structures called pneumatophores. These above-ground roots are filled with spongy tissue and have many small holes in the bark which transfer oxygen to the underground root system. They can also provide structural support for trees in the soft, muddy mangrove soils. Figure 6. The aerial roots of mangroves (Image: Kara Dew)

Figure 6. The aerial roots of mangroves (Image: Kara Dew)

Seed dispersal

Mangroves have buoyant seeds that disperse well in water. Many species produce large numbers of seeds, others produce fewer but relatively larger seeds by providing a large food store for their seeds before releasing them. Most plants produce seeds that germinate in the soil but many mangroves are viviparous (their seeds germinate while still attached to the parent tree). Once germinated safely, the seedling grows either within the fruit or out through the fruit to form a propagule (a seedling). When the propagule is mature, it drops into the water and remains dormant while it floats until it lodges safely in the soil, where it sprouts roots and begins to grow.

Figure 7. Seeds on a mangrove tree (Image: © Shannon Conway)

The importance of mangroves

In the past, mangrove forests have been considerably undervalued. Mangrove wetlands have been considered wasteland or breeding grounds for nuisance insects such as mosquitoes. As a result, many mangrove forests have been cleared, dredged, reclaimed, degraded or otherwise lost.

Our understanding of the value of this habitat has greatly improved over the past few decades and mangrove forests are now regarded as important habitats.

Mangroves provide food

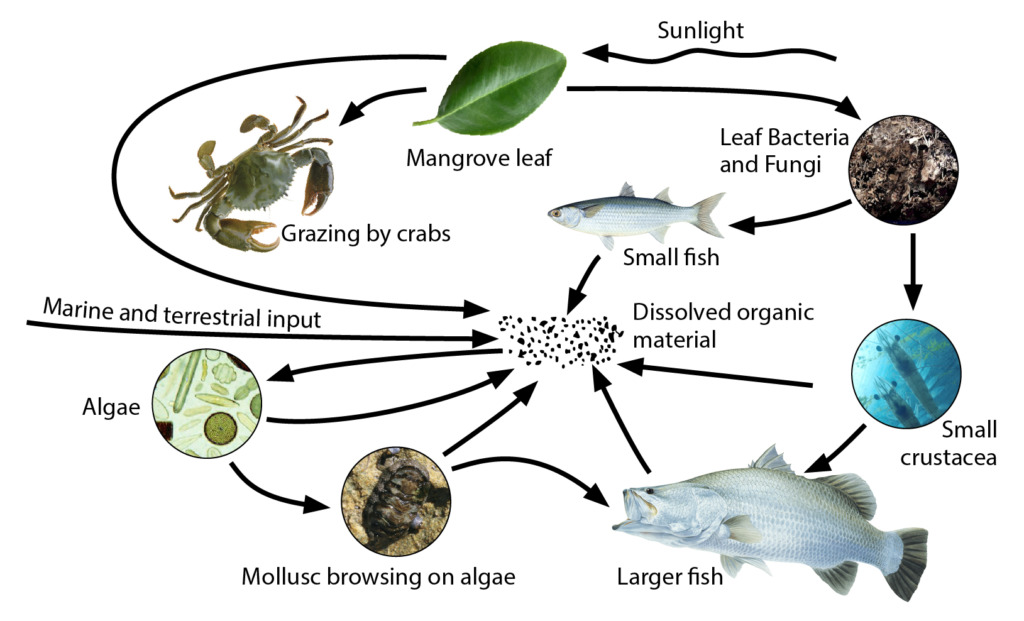

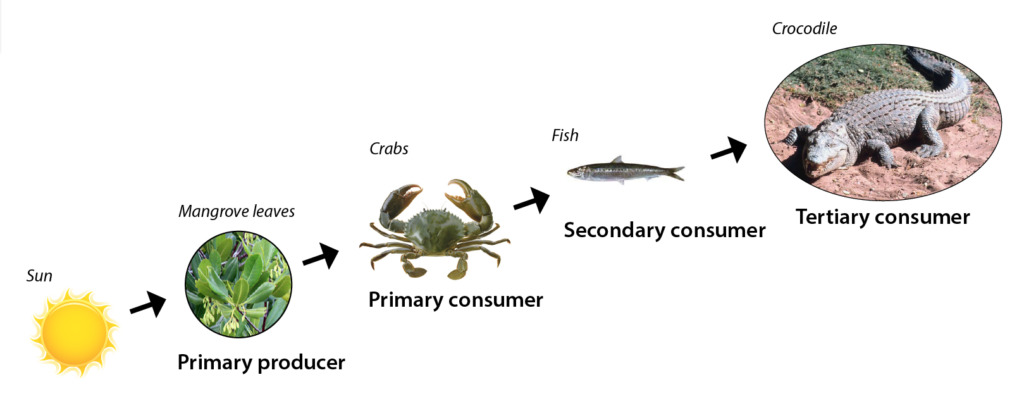

Mangrove forests are part of an ecosystem that supports abundant life through a food chain that begins with the trees (Figure 8). The leaves of a mangrove plant, like those of all green plants, use sunlight to convert carbon dioxide gas to organic compounds (carbohydrates) in a process called photosynthesis. The carbon absorbed by plants during photosynthesis and nutrients taken up by plants from the soil provide the raw materials for tree growth. Tree growth sustains the lives of all other organisms that live in the mangroves.

Figure 8. A simple food chain in a mangrove environment.

Figure 8. A simple food chain in a mangrove environment.

Figure 9. A simple food web in a mangrove environment.

Zero waste

Nothing is wasted in a mangrove forest. Mangrove plants shed large quantities of nutrient-rich leaves which are either broken down by fungi and bacteria, eaten by crabs that live on the forest floor or are carried into marine and estuarine habitats where they are eaten by a variety of fish, crabs and other invertebrates. Decaying organic material breaks down into small particles (detritus) which are quickly covered with a protein-rich bacterial film.

Detritus is the food source for many species of molluscs (snails), crustaceans (crabs, prawns and shrimps) and fish, which in turn, are the food source for larger animals. Nutrients released into the water through the decay of leaves, wood and roots also feed the plankton and algae that form part of the mangrove ecosystem.

Mangroves as habitats

Mangroves are a crucial habitat for the juveniles and adults of many fish species, including many commercially and recreationally important species such as barramundi and threadfin salmon, and shellfish such as prawns and crabs. They are also the popular home of the estuarine crocodile, as well as birds, snakes and molluscs.

Mangroves as a buffer

Mangroves play an important role in preventing coastal erosion. Mangrove communities have the effect of slowing down currents and encouraging an accumulation of mud and sediment that harbours an abundance of invertebrate life. The tangled roots, pneumatophores and trunks of the mangroves absorb the energy of tidal currents and storm-driven wind that create wave action, creating a natural breakwater.

Aboriginal uses of mangroves

For thousands of years mangroves have been an important natural resource for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Many materials were gathered from mangroves and continue to have high cultural significance, and many Indigenous foods are still obtained from mangrove environments, including fish, boring bivalves and mud crabs. Certain mangrove plants are also used as food and medicines. Mangrove timber has been used to construct canoes, paddles, spears and boomerangs.

Threats to mangroves

As more people move into the coastal zone, the risk to mangroves in these areas also increases. Greater pressure is placed on the mangrove environment from both direct and indirect sources such as dumping of waste, trampling by humans, climate change and sea level rise and many other factors.

How can we protect mangroves?

- Like other native flora in WA, mangroves are protected under the Wildlife Conservation Act (1950). Some are also protected within WA’s terrestrial and marine parks and reserves. Please report damage to mangroves to the Department of Environment and Conservation.

- If you are a property owner, fence along the intertidal zone and prevent stock access to mangrove areas.

- Design river-front structures such as jetties or boat ramps to avoid or minimise impacts to mangroves (note: it is

illegal to clear mangroves without a permit). - Avoid walking, riding or driving through mangrove areas, particularly at low tide.

- Dispose of rubbish, oils and chemicals in the correct manner.

- Join a local mangrove monitoring program.

References:

Australian Institute of Marine Science, Mangroves and their products, https://www.aims.gov.au/docs/projectnet/mangroves-and-their-products.html

Department of Agriculture, Australian forest profiles: Mangroves https://www.agriculture.gov.au/abares/forestsaustralia/profiles/mangrove-2019

Duke, N. 2006. Australia’s Mangroves: The Authoritative Guide to Australia’s Mangrove Plants, University of Queensland, Brisbane.

Lee, G.P. 2003. Mangroves in the Northern territory. Department of Infrastructure, Planning and Environment.

Lovelock, C. 1999. Field Guide to the Mangroves of Queensland, Australian Institute of Marine Sciences, Townsville

MangroveWatch, http://www.mangrovewatch.org.au

NSW Department of Primary Industries – Prime Fact 746: Mangroves, http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/236234/mangroves.pdf

Queensland Department of Environment and Heritage (EPA).1994.

Tropical Topics – An interpretative newsletter for the tourism industry: Mangroves I – the plants.

Queensland Department of Environment and Heritage (EPA).1994. Tropical Topics – An interpretative newsletter for the tourism industry: Mangroves II – the animals.

Vocabulary

Biology

The science of physical life dealing with animals and plants.

Bivalve

A class of mollusc (sea snail) that has a shell with two hinged halves, such as clams, mussels, oysters and scallops.

Desalination

The removal of salts from saline water to provide freshwater.

Intertidal zone

The zone between high and low water marks that is periodically exposed to air.

Photosynthesis

The process by which green plants convert carbon dioxide to carbohydrates and oxygen using sunlight for energy.

Pneumatophores (in mangroves and other swamp plants)

An aerial root specialized for gaseous exchange.

Productivity

The production rate of new organic material in an ecosystem.

Saline

Composed of or containing salt.

Taxonomy

The science of classification according to a pre-determined and ordered system.