Fishes are a large and varied group of aquatic animals. Worldwide, there are over 32,000 described species, with over 4,400 in Australia (Australian Museum).

They come in an amazing variety of shapes and sizes. All fishes have the following features in common:

- they live in water;

- have a backbone (vertebrate); and

- breathe using gills.

Most fishes also:

- have scales;

- move using fins; and

- are cold blooded poikilothermic organisms.

There are exceptions to these generalisations, e.g., some species of eels have no fins, lampreys and hagfish have no scales and some shark and pelagic predators are partially warm blooded.

Fishes vary in size more than any other vertebrate groups. The world’s largest fish is the whale shark (Rhincodon typus), which can grow to 20 m long and a massive 34 t in weight. The smallest is arguably Paedocypris progenetica, part of the carp family, measuring only 7.9 mm long.

Figure 1. The world’s largest fish – the whale shark (Rhincodon typus)

There are three main groups (or classes) of fishes:

- bony fish,

- cartilaginous fish, and

- jawless fish.

Bony fish (Class Osteichthyes)

Bony fish represent the largest and most diverse class of fishes, with well over 20,000 species.

As the name suggests, bony fish have a skeleton made from bone. They possess true scales, a single pair of gill openings and an operculum that covers the gills. Most bony fish also possess a swim bladder to control their buoyancy.

Most bony fish reproduce by external fertilisation, with the larvae developing outside of the parent’s body.

Figure 2. A bony fish, the black trevally (Caranx lugubris) has a skeleton made of bone rather than cartilage (Image: © Shannon Conway)

Cartilaginous fish (Class Chondrichthyes)

Sharks, rays, skates and chimaeras belong to a class of fishes called Chondricthyes. All members of this class have skeletons made of cartilage rather than bone. These cartilaginous fish do not have typical fish scales; instead their skin is covered with tooth-like scales called denticles, making their skin extremely tough and abrasive. The gills are also different to bony fish – all cartilaginous fish have between five and seven gill slits.

The teeth of cartilaginous fish are buried in their gums (rather than being attached to their jaws) and the teeth are constantly replaced.

Cartilaginous fishes all reproduce by internal fertilisation, therefore producing small numbers of offspring. They either give birth to live young or lay a few large eggs. Males have claspers that are used to grasp females during mating and insert sperm into the female’s body.

Figure 3. A cartilaginous fish, the black-tip reef shark (Carcharhinus melanopterus) has a skeleton composed of cartilage, as opposed to bone (Image: Ian Scott)

Jawless Fish (Agnatha)

Jawless fish are sometimes given the name Agnatha, which is Ancient Greek for no jaw. Among the most primitive of vertebrates, this group comprises lampreys and hagfishes. Around 50 species exist worldwide.

Jawless fish have long bodies and look like eels. Their skeletons are made of cartilage, not bone. They have no scales.

Lampreys are parasitic. Instead of jaws they have a sucking disc that they attach to their fish host and rasp away at the flesh.They are found in marine and freshwater.

Hagfishes live only in marine waters. They are scavengers and feed on dead fish and other bottom-living animals using a similar method to lampreys.

Figure 4. The pouched lamprey (Geotria australis) is native to rivers throughout the south west of Western Australia from Bunbury to Albany (Image: Neil Armstrong)

‘Fish’ or ‘fishes’?

A group of fish of the same species are called fish. Two or more species of fish are called fishes.

For example, a number of Australian herring swimming together is referred to as a school of fish. If you are referring to two or more different species, e.g., pink snapper and dhufish, the term fishes would be used.

Figure 5. Fish or fishes? Left: A school of fish – Blue fusiliers (Caesio teres) (Image: Lynda Bellchambers). Right: Fishes – A goldspot seabream and multiple bigeye seabream (Image: Rachel Green).

External Anatomy

Figure 6. External anatomy features common to bony fish (Illustrations: © R. Swainston/www.anima.net.au)

Body Shape

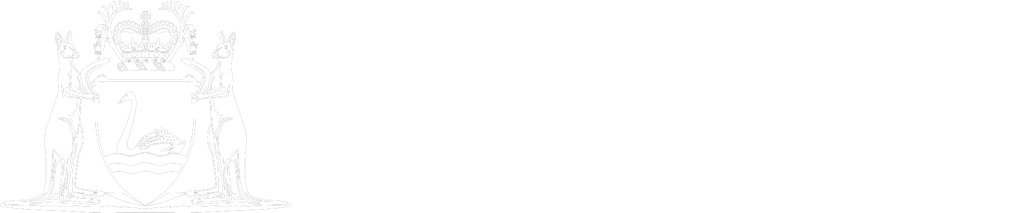

Fish have adapted to live in an enormously wide range of aquatic habitats. The shape of a fish’s body tells us a lot about where it lives, how it feeds and, in particular, how it moves through the water.

Benthic or bottom-dwelling fish (such as flounder and wobbegong) are generally flat in shape, so they can more easily camouflage with the bottom and ambush prey or avoid being eaten themselves. A flat pancake-like shape indicates the fish is able to stay very close to the sea floor.

In contrast, fish that live in reef or coral crevices (for example, butterfly fish) have deep, flat bodies that are highly agile so they can move around without bumping into rocks and reefs. Long slender fish (such as eels and catfish (cobbler)) are able to hide under rocks and among coral, where shorter, stouter-shaped fish would have difficulty in going.

Slow-moving fish with rounded bodies are often protected by spines or armour plating, and may also have poisonous flesh (such as blowfish and white-barred boxfish), owing to their lack of manoeuvrability. Fish with more elongated bodies, such as Western Australian salmon are able to swim very fast for a long time and thus have less need for any special body protection.

Figure 7. Fish body shapes can be broken up into three distinct groups – extreme accelerating (for example mulloway); extreme cruising (such as tunas); and extreme manoeuvring (such as angelfish) (Illustrations: © R. Swainston/www.anima.net.au).

Fins

Fish possess fins to assist movement in the water. The pectoral and pelvic fins are

paired fins – they are the same on both sides of the body. Pectoral fins can be used individually to manoeuvre the fish up, down and sideways. Together, these fins act as brakes and the fish can also use them to swim backwards. The pelvic fins are used for braking and steering.

Fish also have single (unpaired) fins along the centre line, such as the dorsal (back) fins, anal fin and caudal (tail) fin. The dorsal and ventral (anal) fins play an important role by acting as stabilisers – without them the fish would roll over on its side. The fins of most bony fish can be folded flat against the body unlike sharks where the fins are rigid.

The shape of the caudal fin plays an important part with the speed and strength of a fish’s forward movement (locomotion) (Figure 8).

Figure 8. The tail or caudal fin is connected with the speed and strength of the fish’s forward movement and its shape plays an important part (Image: Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development).

The majority of sharks have a heterocercal tail – that is, the upper and lower lobes are not the same size. The upper lobe is longer than the lower lobe which provides lift but is balanced by the pectoral fins.

Scales

Most bony fish have scales. The primary purpose of scales is to give the fish external protection from predators, as well as parasites and other injuries. The scales of bony fish are partly embedded in the skin, and the free parts overlap like tiles on a roof. Fish are usually scaleless when they hatch and develop scales during the first year.

Figure 9. The overlapping scales of fish provide external protection.

Fish scales come in all sorts of sizes and shapes, ranging from small in fast swimming pelagic species like tuna, to large in slow moving reef species like baldchin groper.

Bony fish also have a very important mucus layer covering the body that helps prevent infection. Fishers should be careful not to rub this slime off when handling a fish that is to be released. Handling fish with wet hands or a wet rag will help to protect the mucus covering.

Sharks have small tooth-like scales, called denticles, embedded in their skin.

Lateral line

All fish have a sense for which humans have no parallel. The lateral line is a sensory organ that runs along the sides of the fish’s body, under the skin. It consists of a series of tiny, sensitive cells called neuromasts, which are housed in mucus-filled canals. Small pores in the fish’s skin and scales allow vibrations in the water to pass through to the lateral line. This enables the fish to detect differences of pressure and movement in the water. Nerves connect the lateral line to the ears and the brain.

Figure 10. The lateral line (image: Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development)

Gills

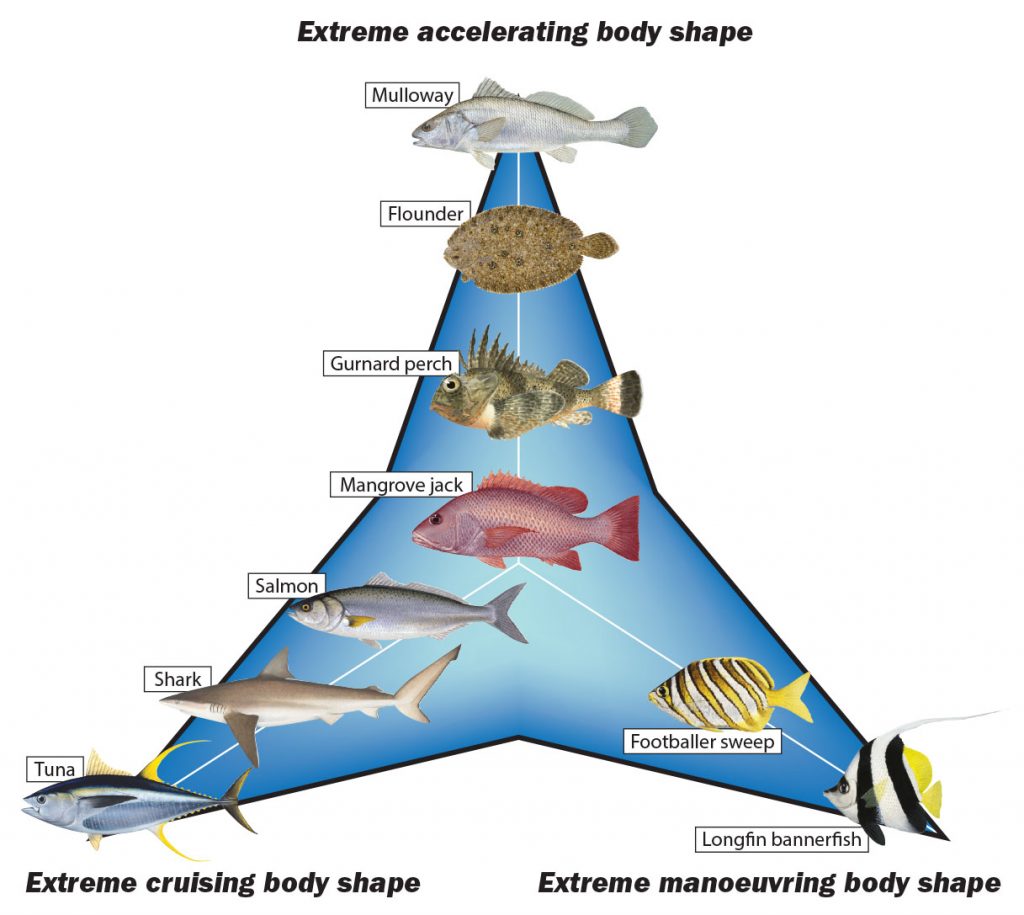

Although they live in the aquatic environment, fish do require oxygen. Fish extract oxygen in the water and diffuse out carbon dioxide using gills. Gills rely on water flowing over them to ensure maximum oxygen uptake.

Most bony fish maintain water flow over the gills by ‘drinking’ water and instead of swallowing it, pushing it out over the gills. Fish that are very active, e.g. sharks, cannot get enough oxygen in this manner and so instead swim with their mouths open, letting water pass in and flow directly over the gills.

In cartilaginous fish, the first pair of gill slits is modified into spiracles, a pair of round openings just behind the eyes. They allow these fishes to take water in even when the mouth is buried in the sand.

Gills are comprised of the gill arch, the gill rakers and the ‘fluffy’ gill filaments (as shown in Figure 11). The filaments are spread over numerous gill plates, thereby increasing the surface area of the gill. The gill arch contains an artery that brings deoxygenated blood to the gill with many capillaries branching from this artery. As oxygen rich water flows over the gills, the oxygen diffuses into the blood while carbon dioxide diffuses out.

The gills are therefore very sensitive and in bony fish are protected by a bony plate known as an operculum (gill cover).

Figure 11. Fish head showing gills and movement of water (Illustrations: © R. Swainston/www.anima.net.au)

Ears

Fish do have ears. They simply don’t require external ears as in many land animals and humans. Instead, only the inner ear is present and is used for balance as well as hearing. Fish can also hear through detecting vibrations in the water.

Eyes

Most bony fish have excellent colour vision. For many, their bodies are accordingly brilliantly coloured and patterned. These bright colours communicate a range of things including aggression, fear, attracting the opposite sex and signalling territorial ownership. Colour patterns may also be for camouflage and disguise, used to hide from or deceive predators.

Bony fish don’t have eyelids. Some shark’s eyes are protected by eyelids, a third protective eyelid called the nictitating membrane, with some also able to roll the eye back into the socket.

Figure 12. The eye of a bony fish.

Nostrils

Fish have a keen sense of smell and can detect small changes in water chemistry. They have a pair of nostrils (called nares) that are used to detect odours in water and can be quite sensitive. In sharks, the nostrils are on the underside of the head rather than on the dorsal surface as in most bony fishes.

Figure 13. The nostril of a yellowtail kingfish.

Mouth

The size and shape of a fish’s mouth provides a good clue to what they eat. The larger it is, the bigger the prey it can consume. The position of the mouth can also indicate whether a fish consumes prey from the surface, sea floor, or in front of it.

Superior– the mouth is positioned towards the surface and the fish feed on what is above them, e.g., garfish and snook.

Terminal– the mouth is positioned in the middle of the head and the fish either chase prey or feed on what is ahead of them, e.g., tuna and tailor.

Inferior– the mouth is positioned towards the bottom and the fish prey upon or scavenge/graze benthic food sources, e.g., whiting and cobbler.

Figure 14. The position of a fish’s mouth can provide some clues to the possible diet and prey of each species (Illustrations: © R. Swainston/www.anima.net.au)

Fish have a sense of taste and may sample items to taste them before swallowing if they are not obvious prey items. Fish may or may not have teeth depending on its position in the food chain and food preferences.

Cartilaginous fish have teeth embedded in their gums, rather than attached to their jaws. The teeth are constantly replaced and most sharks have several rows of developing teeth behind their main row, waiting to be used whenever a tooth is broken or dislodged.

Reproductive organs

Male sharks have claspers that are used to attach to females during mating and insert sperm into the female’s body. All cartilaginous fish reproduce by internal fertilisation.

INTERNAL ANATOMY

Swim bladder

Most bony fishes (adult flounder and some bonito are an exception) have a swim bladder for buoyancy control. The amount of gas contained within the bladder is adjusted to allow the fish to move up and down in the water column while conserving energy. In some species the swim bladder is also used in hearing and sound production.

Sharks don’t have a swim bladder. Instead sharks have oily livers that are lighter than water which assist the shark in achieving neutral buoyancy.

Otoliths

The otolith (sometimes referred to as the ear bone) is the fish’s inner ear, assisting with balance and enabling them to listen to sound waves that travel through the water. Fishery scientists are able to determine the age of a fish by counting the number of growth rings that are deposited in the otolith.

How do fish hear? (Video courtesy of Woodside)

Heart

The heart is a muscular organ that pumps blood throughout the body. In fishes, blood is circulated by a 2-chambered heart – deoxygenated blood enters the first chamber of the heart from the body. It is then pumped to the second chamber before passing through the gills where it loses carbon dioxide and receives a fresh supply of oxygen. The oxygenated blood is carried back to the body by blood vessels called arteries. The arteries branch out into capillaries, which then collect into larger vessels, veins, carrying deoxygenated blood and dissolved carbon dioxide back to the heart to complete the cycle.

Nearly all fish species are cold blooded poikilothermic organisms, which means that their blood temperature varies with the water temperature around them. Some fish species, such as the white shark and yellowfin tuna, are partially warm blooded and are able to raise their body temperature a few degrees above the temperature of the surrounding water. In some fish species, such as swordfish, they have adapted a specialised blood vessel structure that allows them to increase the temperature of their brains and eyes, presumably to assist with hunting in deep, cold water.

Liver

The liver produces enzymes to aid in digestion. It is also a storage area for fats, blood sugars and vitamins and breaks down toxins and old blood cells.

In sharks, the liver is particularly large and rich in oil.

Stomach

The stomach is where digestion commences. All fish have a one-way digestive system. Food enters the mouth and travels via the oesophagus to the stomach. From the stomach, it is passed into the intestine for further digestion. Digested wastes are eliminated from the intestine via the anus.

Intestine

The intestine is the main site of digestion and absorption of nutrients. Undigested material exits the body through the anus.

As a general rule, bony fish with short intestines are carnivorous and those with long, coiled intestines are herbivorous, as fibrous plant materials are harder to break down.

The intestine of cartilaginous fish contain an area called the spiral valve that acts to increase the internal surface area of the intestine.

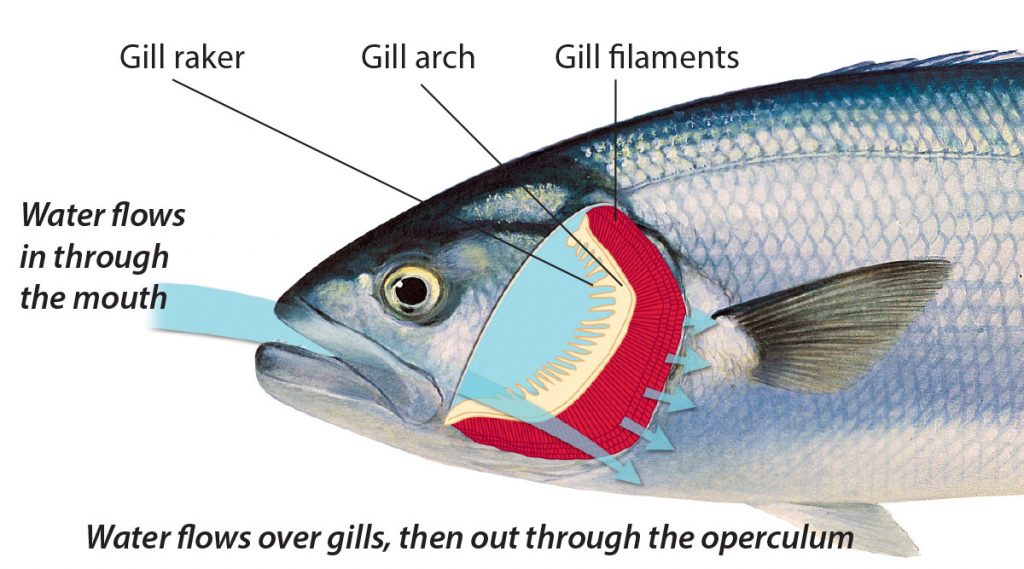

Reproductive organs

The reproductive organs of bony fish are referred to as gonads. These organs are usually paired. Female gonads are called ovaries and produce eggs. They are usually pink, red or orange in colour and covered in numerous blood vessels. Male gonads are called testes and produce sperm. They are usually white/cream or grey in colour.

Figure 15. Left – ripe male gonads. Right – ripe female gonads.

Kidney

The kidneys are one of the organs that assist with excretion and regulation of water balance. In bony fish, salts that are absorbed are excreted by the kidneys. They also conserve water by only producing small amount of urine.

In cartilaginous fish, the kidneys also control the amount of urea retained in the blood that aids in making the blood concentration closer to the of seawater.

References:

Australian Museum 2018, Fishes, https://australianmuseum.net.au/fishes [28 June 2018]

Australian Museum 2018, What is the smallest fish? https://australianmuseum.net.au/fwhat-is-the-smallest-fish [28 June 2018]

Castro, P. & Huber, M.E. 2008 Marine Biology, 7thEd. McGraw-Hill.

Chen et al.1997 and Chen et al.2002. Cited in Rowat & Brooks (2012) A review of the biology, fisheries and conservation of the whale shark Rhincodon typus. Journal of Fish Biology, Vol. 80 (5), pp 1019-1056.

Helfman, G.S., Collette, B.B., Douglas, E.F. & Bowen, B.W. 2009, The diversity of fishes: Biology, Evolution and Ecology, 2ndEd. Wiley-Blackwell.

Moffatt, B., Ryan, T. & Zann, L. 2003, Marine Science for Australian students. Wet Paper Publications, Queensland.

Parish, S. 1997, Amazing facts about Australian Marine Life. Steve Parish Publishing, Fortitude Valley, Queensland.

Vocabulary

Pectoral fins

Pair of fins situated just behind the head in fishes that help control the direction of movement

Pelagic

Associated with the surface or middle depths of a body of water.

Pelvic fins

The first pair of ventral fins of fishes.