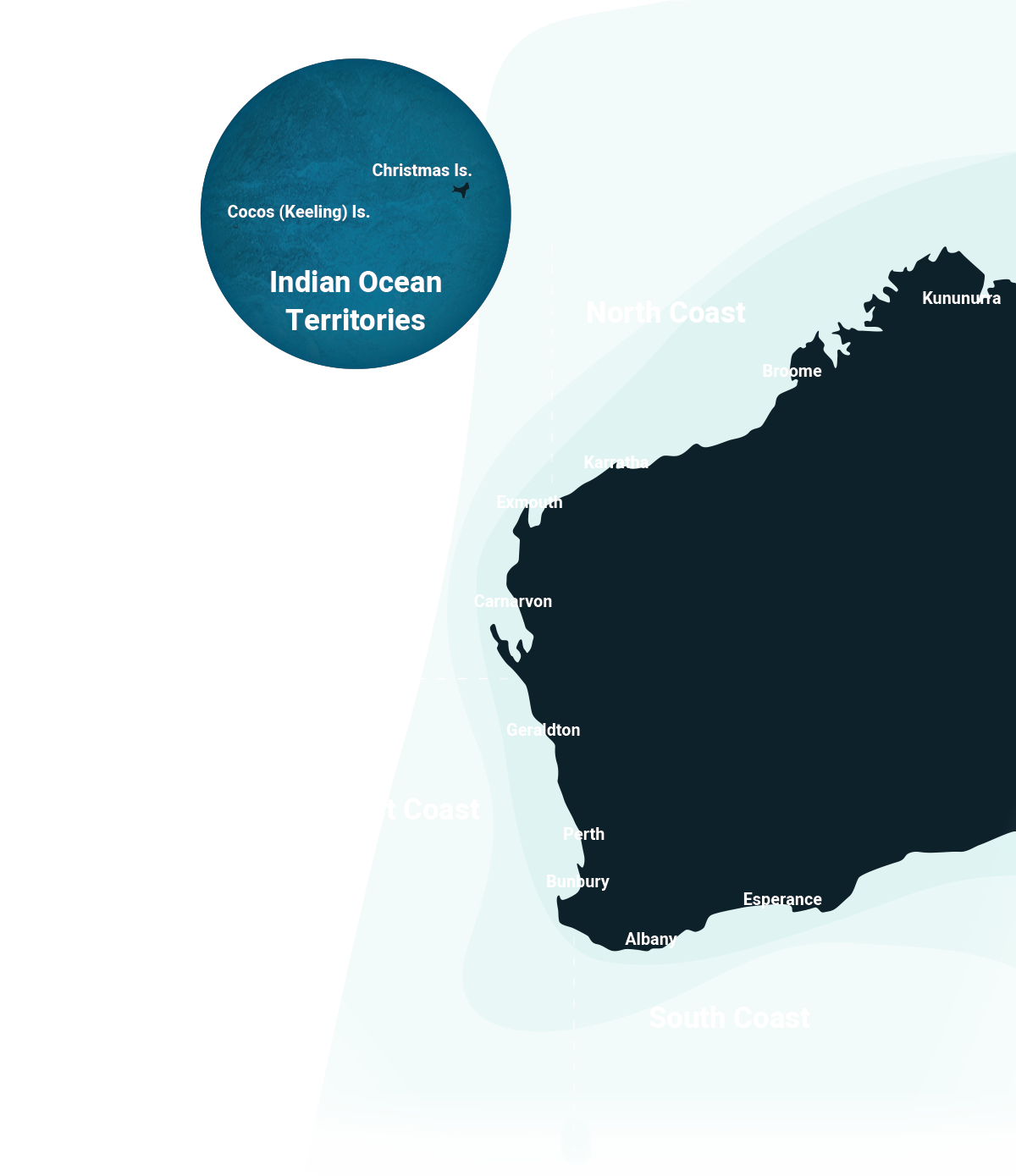

Australia’s external territories of Christmas and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands are home to marine species, habitats and migration events that occur nowhere else in the world!

Referred to as the Indian Ocean Territories (IOTs), the remote location of Christmas Island and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands is the key to their unique and spectacular marine biodiversity. With Christmas Island located 2,600 kilometres north west of Perth, and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands 2,900 kilometres, Exmouth’s Northwest Cape is the closest point to the IOTs on Western Australia’s coast.

Christmas Island is the tip of an undersea volcano that reaches out of the ocean to a height of 361 metres above sea level. In comparison, the Cocos (Keeling) Islands are formed by two coral atolls comprised of 27 islands. Twenty-six of the islands form a horseshoe shape around a central lagoon with a single island lying 27 kilometres north of the main atoll.

Resulting from the last Ice Age

About 18,000 years ago, during the last Ice Age, Australia was connected to Papua New Guinea and many Indonesian islands (especially the Sunda Islands) by land bridges. These land bridges separated the Indian and Pacific Ocean regions and acted as a barrier that prevented the mixing of marine species from each region. Towards the end of the last Ice Age, melting ice caused a rise in sea levels that covered the land bridges. As a result, these land bridges now lie under hundreds of metres of water, with species from each region mixing freely.

The suture zone between the Indian Ocean Bioregion and the Indo-Pacific Bioregion where the Indian Ocean Territories lie.

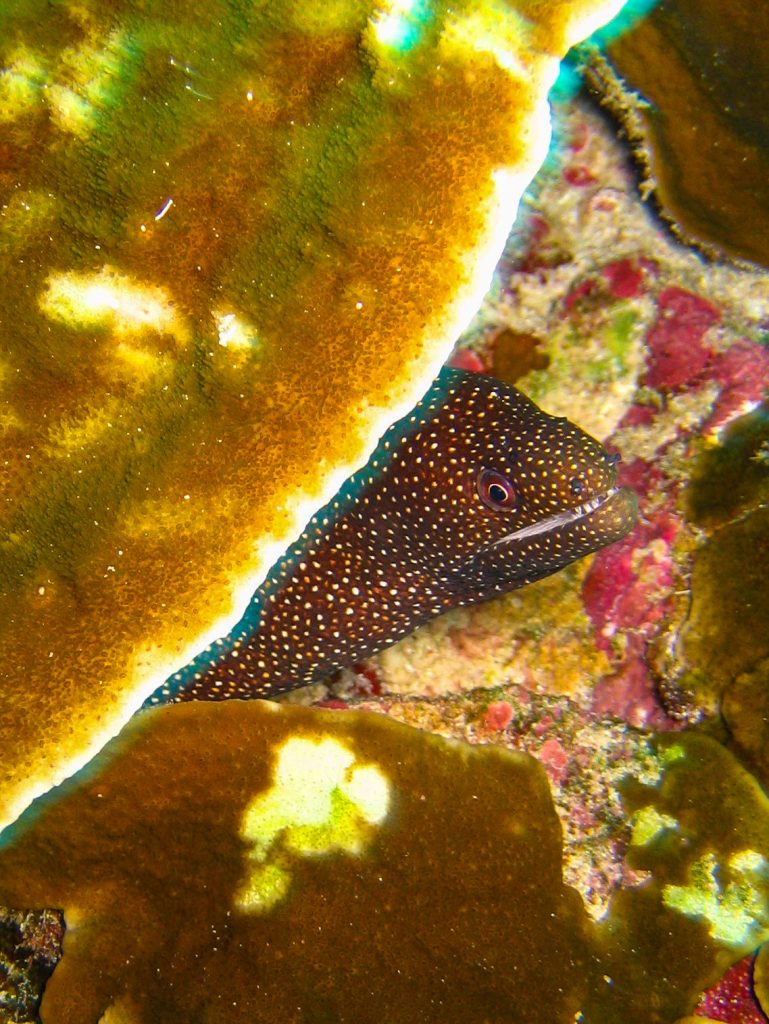

Christmas Island and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands lie directly in the middle of where these two bioregions now mix, or overlap. This is called a ‘suture zone’. Suture zones are quite rare in the marine environment, making Christmas Island and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands home to very unique underwater worlds.

Discovery of this suture zone came about from the identification of 15 hybrid coral reef fish species at the IOTs. This is the largest number of hybrids ever found in the marine environment. A hybrid occurs when closely related species (for example tigers and lions or horses and zebras) mate and produce offspring. The mating of the two species can happen as a result of one of the two species being rare. This means that when a fish can’t find a member of the opposite sex of the same species to mate with, it will mate with a member of the opposite sex from a different, but similar, species instead. Butterfly fish are one of the most common groups of reef fish that hybridise.

An area of isolation

Not only are the IOTs remote from mainland Australia, they are also remote from any other land mass or coral reef environment. The reefs off Indonesia’s Java coast are the closest coral reefs to the IOTs (approximately 350 kilometres north of Christmas Island). The distance between the coral reefs at the IOTs and coral reefs off Indonesia and Australia means that the fish populations at the IOTs can become isolated. This is because the distance over which fish from other reefs would have to travel to join the fish population at the IOTs is far too great. Fish stocks that are isolated in this way can suffer from overfishing. When too many fish are taken out of a fish stock, the population ends up with not enough sexually mature adults to produce young to keep numbers sustainable. As a result, taking too many fish out of IOTs waters can have a serious impact on the long-term sustainability of fish stocks in the region.

The drop off

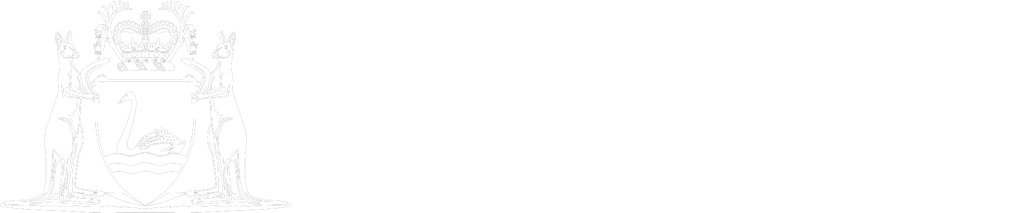

While the land terrain of Christmas Island and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands are very different, there are similarities in their underwater environments. It is these similarities that set the waters of the IOTs apart from the waters off WA’s coast. At the IOTs, the seafloor ‘drops off’ very close to shore, quickly reaching depths up to 3,000 metres. At Christmas Island, the drop-off can occur as close as one metre from the cliffs while at the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, it lies just beyond the fringing reef. The drop-off at both Islands is very accessible by small boats.

In comparison, along the Western Australian coast, the drop-off, where deep water fish are found, occurs much further from shore. Bigger boats are needed to access the drop-off and the weather conditions need to be just right to allow fishing so far from the coast. Not only does the proximity of the drop-off to the shore make the waters of the IOTs unique, but so does the combination of other marine habitats around the Islands. At Christmas Island, intertidal, shallow-water, deep water and pelagic fishes are all found close to shore. At the Cocos (Keeling) Islands the same groups of fish species are also found but with the addition of lagoonal species. Fishers at Christmas and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands are in the special position of having relatively easy access to diverse groups of fish species in a way of which mainland fishers can only dream.

A unique marine environment

The islands of the IOTs each have their own distinctive features, both above and below the water – clear waters with exceptional visibility, abundant and healthy coral reefs, along with fish and migration events not seen anywhere else in the world. However, the unique and isolated nature of the island’s marine ecosystems also makes them vulnerable to damage – which can occur from both natural and human causes. Coral reefs often take the full force of severe storms and cyclonic events. During the doldrums, still, warm waters and coral spawning events can result in fish kills in which fish are deprived of oxygen and many thousands can perish.

Marine environments have been experiencing these natural events for thousands of years and have the ability to restore balance to ecosystems in a ‘recovery’ period. However, human-induced events,such as coral bleaching and overfishing, are not part of natural cycles and their impacts can have devastating effects on the long-term health of coral reef ecosystems.

View all Indian Ocean Territories resources