The common blowfish or ‘blowie’ (also known as the weeping toadfish or banded toadfish) is abundant in estuaries and coastal waters throughout south-west Western Australia. It is often regarded as a nuisance because it gobbles bait, making it hard for fishers to catch other species of fish. Unlike true ‘pest’ species, blowfish are not actually an introduced species but are native to our marine environment. Blowfish play a vital role in marine ecosystems, keeping them clean by eating scrap, bait and berley.

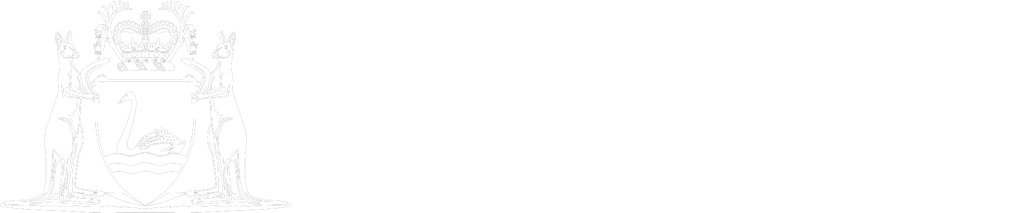

Figure 1. Common blowfish Torquigener pleurogramma (Illustration © R.Swainston/www.anima.net.au)

Size and distribution

Common blowfish can grow up to 22 centimetres long. They have a distinctive horizontal stripe along their side, broad vertical bands and irregular grey-green spots on the dorsal surface.

Common blowfish occur abundantly in schools around much of the southern half of Australia. They are mainly found along WA’s lower west coast but are sometimes seen as far north as Coral Bay and as far east as Esperance.

Figure 2. The common blowfish is widely distributed around much of the southern half of Australia. (Image: DPIRD)

Common blowfish are a marine species – found in the ocean and in the saline water of estuaries. In the Swan River Estuary in Perth, blowfish are most abundant near the estuary mouth at Fremantle, moderately abundant in the middle of the estuary and rare in the upper estuary. They usually prefer shallow water up to four metres deep but, in times of very high abundance, can be found at greater depths.

Toxic family

Common blowfish belong to the family Tetraodontidae, which includes well over 100 species of toadfish and pufferfish, of which more than 25 are found in WA. Members of the Tetraodontidae family typically have torpedo-shaped bodies with small scales or scales absent, sometimes embedded with small spines. They also lack pelvic fins and have fused teeth that form a beak.

Another characteristic of this family is a highly lethal toxin, called tetrodotoxin, present in the fishes’ skin, flesh and internal organs.

In Japan, fish from this family are known as ‘fugu’ and are considered a delicacy. Young chefs spend years learning how to prepare fugu. However, each year, a few people still die from eating poorly-prepared fugu dishes.

In Australia, pets have died from eating blowfish washed up on beaches or left behind by fishers. They may appear to be a smelly or tasty treat to your pets, if blowfish are chewed or your pet may vomit soon afterwards and show signs such as drooling, panting, dullness, and lethargy. This may progress to wobbliness/weakness, usually starting in the legs.

The toxicity can progress to paralysis and ingestion of blowfish by pets can be life threatening. If you suspect or notice that your pet has had contact with a blowfish, seek immediate veterinary attention.

A relative of the common blowfish, the silver toadfish (or northwest blowfish), is found widely throughout the tropical Indo-Pacific region. Commonly encountered in northern Australian waters, they may also be seen of WA’s lower west coast as far south as Cape Naturaliste near Dunsborough. Growing up to 88 centimetres long, they have a silvery stripe down its body and a greenish-coloured back with dark spots. They are an aggressive species that can inflict serious bites.

Figure 3. Silver Toadfish Lagocephalus sceleratus (Illustration © R.Swainston/www.anima.net.au)

Globe fish are also related to blowfish. Globe fish are distinguished by their more rounded body shape, and long yellow spines on their head and body that become erect if their body inflates. They also have four dark bars down their sides and yellow markings at the base of their spine.

Figure 4. Globefish are relatives of blowfish (Image: Carina Gemignani)

Serious scavengers

Blowfish are opportunistic feeders, meaning they will eat just about whatever is going. A study in the Swan River Estuary found that young blowfish up to 13 centimetres in length mainly eat small crustaceans (for example, prawns) and marine worms known as polychaetes. Older blowfish eat bivalve molluscs, such as mussels. Of course, as any fisher knows, blowies will also form a feeding frenzy the minute berley and bait land in the water!

Some larger fish feed on blowfish, apparently without ill effect from their toxin. Blowfish have been found in the stomachs of tuna, tailor and mulloway.

Life of a blowie

Blowfish get their name from their ability to inflate their abdomens with water. This defence mechanism enables blowfish to look bigger and so warns off potential predators. Blowfish also inflate their abdomens with air on removal from the water and may have difficulty deflating. It is therefore best to put them back as quickly as possible.

Much is unknown about the life cycle of blowies. Most research conducted on blowfish in Western Australia has occurred in the Swan River Estuary.

These studies have shown that they live to at least six years old and reach sexual maturity at about two years of age.

Mature blowfish migrate out of the Swan River Estuary to spawn in shallow coastal waters along Perth’s coastline between October and January, with the peak spawning period being November to December. At these times, large schools of blowies have often been observed by fishers passing out to sea through the Fremantle heads.

Males and females release their sperm and eggs into the water where fertilisation occurs, and the fertilised eggs develop into larvae. Once the larvae have developed into juvenile blowfish between five and seven centimetres long – at about seven to nine months old – they enter the estuary and then stay there until they are sexually mature.

A single stock

It is thought that blowfish larvae originating from various spawning events along the coast are transported and mixed by ocean currents, leading to the creation of a single genetic stock along WA’s lower west coast. This means that blowfish spawned in the ocean from Swan River Estuary stock may enter the estuary as juveniles or stay in the ocean – or travel to nearby sheltered coastal waters such as Cockburn Sound at Rockingham.

Studies show blowfish grow at different rates in different locations. After one year in the Swan River Estuary, blowfish are an average 8.5 to 10 centimetres in length, compared to 7.4 centimetres at Rockingham, and 6.5 centimetres at Jurien Bay and Dongara.

Blowfish bonanza?

Many people think that there are more blowfish today than there were in the past. A decline in rainfall in south-west WA since the mid-1970s (leading to larger saline areas in estuaries providing ‘marine’ conditions suitable for blowies) is one possible reason for an increase in blowie numbers.

However, historical records show that there were also periods of high blowfish abundance in the past. In 1973, fishing writer Ross Cusack observed that blowies had occurred in large numbers along the WA coast during the periods 1930–1935 and 1954–1955. In the late 1960s, there was a period of respite with fewer blowfish around, but by the early 1970s, the high numbers were back, he noted.

“Blowies have infested the entire WA coastline from east of Esperance, north to Shark Bay and they now thrive in every estuary. The time has come to wonder just how bad our blowfish plague can get.” (Ross Cusack, 1973)

The problem of high blowfish numbers is clearly not new. However, it is possible that the current period of high abundance has lasted an unusually long time.

Avoiding blowfish

Leaving blowfish on the shore or jetty is cruel and does nothing to reduce their numbers. It could also lead to the fatal poisoning of pets such as dogs.

Figure 5. Dead blowies are commonly left on beaches and jetties (Image: Gilbert Stockman)

Here are some tips to help avoid catching these so-called ‘nuisance’ fish:

- try using bigger hooks and less berley;

- blowfish appear to like real food, rather than lures;

- blowfish often gather around fishing spots, so try moving somewhere else;

- take your unused bait home rather than throwing it into the water, or dispose of it in a bin well away from the water.

Related resources

Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, 2023. Blowfish (Torquigener pleurogramma) Information for fishers and pet owners, https://www.fish.wa.gov.au/Documents/recreational_fishing/additional_fishing_information/blowfish_info_fishers_and_pets.pdf

References

Bray, D.J. 2021, Torquigener pleurogramma in Fishes of Australia, accessed 28 Mar 2023, https://fishesofaustralia.net.au/home/species/883

Bray, D.J. 2018, Lagocephalus sceleratus in Fishes of Australia, accessed 17 Apr 2023, https://fishesofaustralia.net.au/home/species/868

Busselton Jetty, Toadfish; Banded, accessed 17 April 2023, https://education.busseltonjetty.com.au/fish/toadfish-banded/

Cusack, R. 1973 Menace Under the Water. (in The West Australian)

Edgar, G.J. 2005. Australian Marine Life: The plants and animals of temperate waters (Revised edition).

McGrouther, M. 2019, Silver Toadfish, Lagocephalus sceleratus, Australian Museum, accessed 17 April 2023, https://australian.museum/learn/animals/fishes/silver-toadfish-lagocephalus-sceleratus/

National Geographic Kids, Pufferfish, accessed 17 April 2023, https://kids.nationalgeographic.com/animals/fish/facts/pufferfish

Potter, I.C., Cheal, A.J. & Loneragan, N.R. 1988. Protracted estuarine phase in the life cycle of the marine pufferfish Torquigener pleurogramma.

Smith, K.A. 2006. Fisheries Research Report No. 156. Review of fishery resources and status of key fishery stocks in the Swan-Canning Estuary.

Vocabulary

Abundance

Number of fish in a stock or population

Bivalve mollusc

A class of mollusc (sea snail) that has a shell with two hinged halves, such as clams, mussels, oysters and scallops

Crustaceans

Animals with hard, jointed external skeletons, such as crabs, shrimp, lobster and prawns

Larva (plural: larvae)

The stage of a fish between hatching and becoming a juvenile

Native

Exist naturally in an area or location

Pelvic fins

The first pair of ventral fins of fishes.

Pest

An unwanted, destructive or damaging organism.

Polychaete

A class of worms, usually marine.

Spawning

The release or depositing of spermatozoa or ova, of which some will fertilise or be fertilised to produce offspring.

Stock

A population of fish within a certain geographical area where members of that population breed with each other

Toxin

A poison produced by the cells of plants and animals